Field Notes

Volgermeerpolder (repost)

Many years ago, when I first passed it, I thought it was a secret military camp or something like that. From the outside it had a certain darkness to it. But later, when fences went down and I understood I could enter the area, I found nothing but a big, flower-filled meadow inside.

Since this land is a little higher than the surrounding fields, it has an almost mountain-like feel. The low, linear horizon surrounding it is interrupted only by a few farms and the blunt tower of Ransdorp, once drawn by Rembrandt, probably when it was the temporary hometown of his housekeeper and lover, Geertje Dircx. Also the high risers of Amsterdam are there in view, far away, the church towers of Zunderdorp, Broek in Waterland and Monnikendam, and to the east one can see what I think must be the buildings of a completely different city, Almere, though the latter structures are only visible on the clearest days.

There is history in this blooming hill. A poisonous one. Buried in the ground lies some extremely toxic materials, among them dioxins. Barrels of chemicals were unlawfully deposited here by big business in the 1960s. Thousands of barrels. Since the area earlier had been used to dig out peat to be dried for fuel, it already had big sunken areas, and I guess it was these that were used by the city and by commercial enterprises as a land fill. Ironically peat, like the one that was first was removed to be burned, is one of the best capturers of carbon dioxides. It is a ground that was marred twice.

Then in recent times, and through major endeavors, the toxic ground was covered in layers of huge sheets and masses of soil. On top came fresh water and vegetation. To make new peatland probably takes a very long time, but there are plenty of wet areas, and to one side a wide, dry grassland with a path across. A crossing over some water is built as concrete stepping stones, otherwise there are few signs of it being a public park. The borders aren’t marked and there are no visible barriers between the hill and the lower landscape.

The grass is kept mostly uncut to the pleasure of beasts and birds. How well the beasts in the ground are sealed in, I wouldn't know. But this year, for the first time, I saw one of the marsh orchids that are plentiful outside the hill, also grow on it. Like an old garment most carefully mended to last many more seasons, it seems to work for now.

Every 5 years

After all this holiday bliss it’s a little hard to step of the train in Fulda, Germany, after a change over in Munich. We are staying in a sad budget hotel, and even if the city is full of huge baroque buildings, it feels like a waiting room for us. I forget to take any pictures. It’s not always easy to find 3-bed rooms at an affordable prize, so instead of staying in the home city of Documenta, Kassel, 45 minutes further north, we stay here, and take the train back and forth the next day. We’re getting the most out of our inter rail tickets - and I must admit I still treasure out time on trains.

While I hadn’t heard much about the Venice Biennial, news about this years Documenta 15 has been hard to miss. It has been ridden with controversy, and everyone seem to have different versions of what went on. It’s curated by the artists group Ruangrupa and they invited other groups that then invited others. Where the “The Milk of Dreams” in Venice was the most tightly curated show possibly, this is more loosely put together without clear lines of responsibility. In this organizational web a derogatory picture slipped through that should not have been in the show, and the curator group was slow to remove it. As a result one of the few very famous German artist in the show pulled out.

It’s only my fourth time to Documenta, but since it happens every 5th year the visits covers 20 years of my life. I see many older Germans in the crowds. Some must have come here for 50 years. I love this kind of tradition. Life changes and art changes intertwined.

It might be loosely put together, but the strategy of collaboration is present in every presentation. It is both frustrating and freeing to see a show where the focus on individual artists are almost not there. Frustrating because things are less easy to pin and categorize, freeing because one can leave any name dropping skills (or rather lack thereof) behind.

But beyond the framework of collaboration the themes vary. From home there is The Black Archive that among other things have been important in the movement to stop the Dutch tradition of Swarte Piet. Their presentation is like a summary of some of their work, but also a useful library the visitor can take advantage of.

In the Ottoneum, the nature history museum that is used as a venue, they seem good at asking to get something back from the visiting Documenta artists. 10 years ago Mark Dion made a handcrafted wooden shelf system for their collection of 18th century books about trees made out of the same tree type they describe. This time a group have transformed their garden pond from a chlorofied fountain to a more useful ecosystem. Handmade terracotta tiles now support local plants. When the plants have developed a strong root system to support themselves, the clay will slowly have dissolved.

Even if singular artists aren’t in focus, there are many singular works. One work is about the possible contradictions between traditional ways of nature preservation and modern nature sanctuaries in Congo. An interviewer asks an old farmer: -Who owns your land? She laughs and answers -You maybe say it’s the state, but I say it’s me. -How big is your land, the interviewer asks, how many hectares? -Oh, my bush is big. When I get tired, that’s where it stops.

I take this as a sign. The show is big, but I am tired, and that’s where it stops for me. I go and sleep in a beach chair.

Well, I do see more works, like one about recycling clothes that makes me want to never bring any clothes to recycling containers again (I should get a loom to wave rugs from all our old clothes).

And then we eat dinner at the Alex café.

Tyrollean morning

The afternoon train back over the alps is old and warm (this is a week ago now - delayed posting). We share car with a Mexican professor on her way to summer school, and it’s our first time getting to know a fellow traveler. First up on the Italian side.

Then down on the north side of the Brenner pass. The landscape is both majestic and familiar. The main difference to the childhood mountains is that these are much higher. But because we are so much further south, the vegetation is similar. Just the shape of the spruce is different. These are more pointy on top, and their skirt shorter below.

We arrive in the tiny city Kufstein late in the evening. The hotel is small, family run with care. The breakfast in the morning is huge, with sausage from meat hunted by the hotel people themselves, apfelstrudel and mixed nuts in honey. We eat enough to equal out all the mornings we eat backpack-crushed cookies as our morning meal.

Kufstein has one big attraction, and it literally hovers over the city. A medieval fortress high up on a cliff.

One can take a little steep lift, but I prefer the stairs.

We spend most time in the round structure at the very top. It was used as a prison for mostly political prisoners. Theorigne in the time of the French Revolution…

… and in the mid 19th century among many other revolutionary Hungarians, the activists Blanka Telaki and Klara Lövey. Kept not only high up in a tower cell, but even far away from home and possible support.

There are several different museums tucked into the complex. One has of Stone Age findings from caves in the area, and animals I can’t completely believe are real.

It’s a short stay in Austria, but the kids desire for Winer-schnitzel is covered, while we adults eat knödel a little more skeptical, before we leave Austria and Tyrol after less than 15 hours. We travel fast, but are so focust on each place it feels like time stands still.

Stars shining on a blue sky

Padova is just a short train ride away from Venice. We struggle carrying the backpacks in the scolding sun, but as soon as we enter the bar-filled, grotto style park where both the Scrovegni Chapel and our apartment for the night is located, we feel better.

Instead of seeing the city, we hang out in the park and eat pizza at the family restaurant we live above.

Early up next morning to see Giotto’s chapel. The roof has stars that mirrors the chapel of When the Body says Yes that we saw the day before - and even the colorful textiles and all the bodies filling the the pictures below seem oddly related. Happy accidents that makes it look like it’s a well curated trip.

The story of Maria’s parents Anne and Joachim touches me the most. The struggle to conceive a child feels like such a contemporary story, and their face expressions are fresh as the day they where made (720 years ago). They bend awkwardly toward each other to kiss, like they are close but also shy. Not for the other, they are clearly close, but as if they know we stand here now watching them.

In the end Joachim goes away for 5 months, and when he comes back, Anne is pregnant. He embraces the situation, and the whole New Testament then follows. But since this elderly couple are given so much space, it is almost like it was Anne and Joachim who pushes the whole and well known story forward.

After the familiar scenes, we are brought into the future. The good - and the bad:

Colorful salvation or gray and brutal condemnation. The kid finds it most striking that a poor guy is about to loos his precious parts to a devouring devil. I don’t know if it was painted as scary or funny, most likely the first, but I like to think the latter. A little horror comedy in the middle of all the gloriousness.

There are all kind of bodies, pretty dressed up ones or naked childlike ones, looking sweet as they climb out of their colorful box-like coffins, on their way to eternity.

Frescoes and watercolors have so much in common. Both are techniques where the first stroke stands. You can’t redo or change. The moment of creation and the motief share the surface, and makes it feel so immediate and close. Relationships, interactions, friendly and less friendly meetings, stories as old when they where painted, as the paintings are old now, and still relatable.

We tourists are only allowed inside for ridiculously short 15 minutes, and a strikt guards job is to chase us out to let a new group in. No one wants to leave.

The picture gallery adjacent to the chapel is also fun. Quite a selection is served on plates:

A brake at a coffe kiosk, first just a snack, we can’t help ourself and also have the most delicate tiny cakes.

The kids drawing pad is always with.

Then it’s the cathedral where there are long lines to honor St Anthony - the saint of lost things, even lost people. No wonder he’s a popular one.

Last stop is the botanical garden, designed in 1545 it is the oldest university garden in the world in its original form.

A remarkable place, with a circular shape that both reminds me of an old pattern, like the one of a Persian rug, and a modern one, like scientific graphics. Wasn’t that what the Renaissance was all about, studying the past to create spaces for new knowledge?

A garden is never the same, and there aren’t much indication of which plants are the same types as in the beginning. But the plant selection isn’t spectacular, and I wonder if that is because it’s kept similar to its original collection.

No time to search for restaurant, because our train leaves soon, but the first and best place on our path is really also the best. Wonderful friendly service, perfect food and Prosecco. I smile too much, and I almost cry again. A good thing we’re leaving Italy. This wonderfulness is going to my head.

Two Venice Pavilions: Body Interactions

Some quick notes on two of the pavilions at the Venice Biennial, both with artists I know about from home; the Finnish and the Dutch pavilions, works by Pilvi Takala and Melina Bonajo.

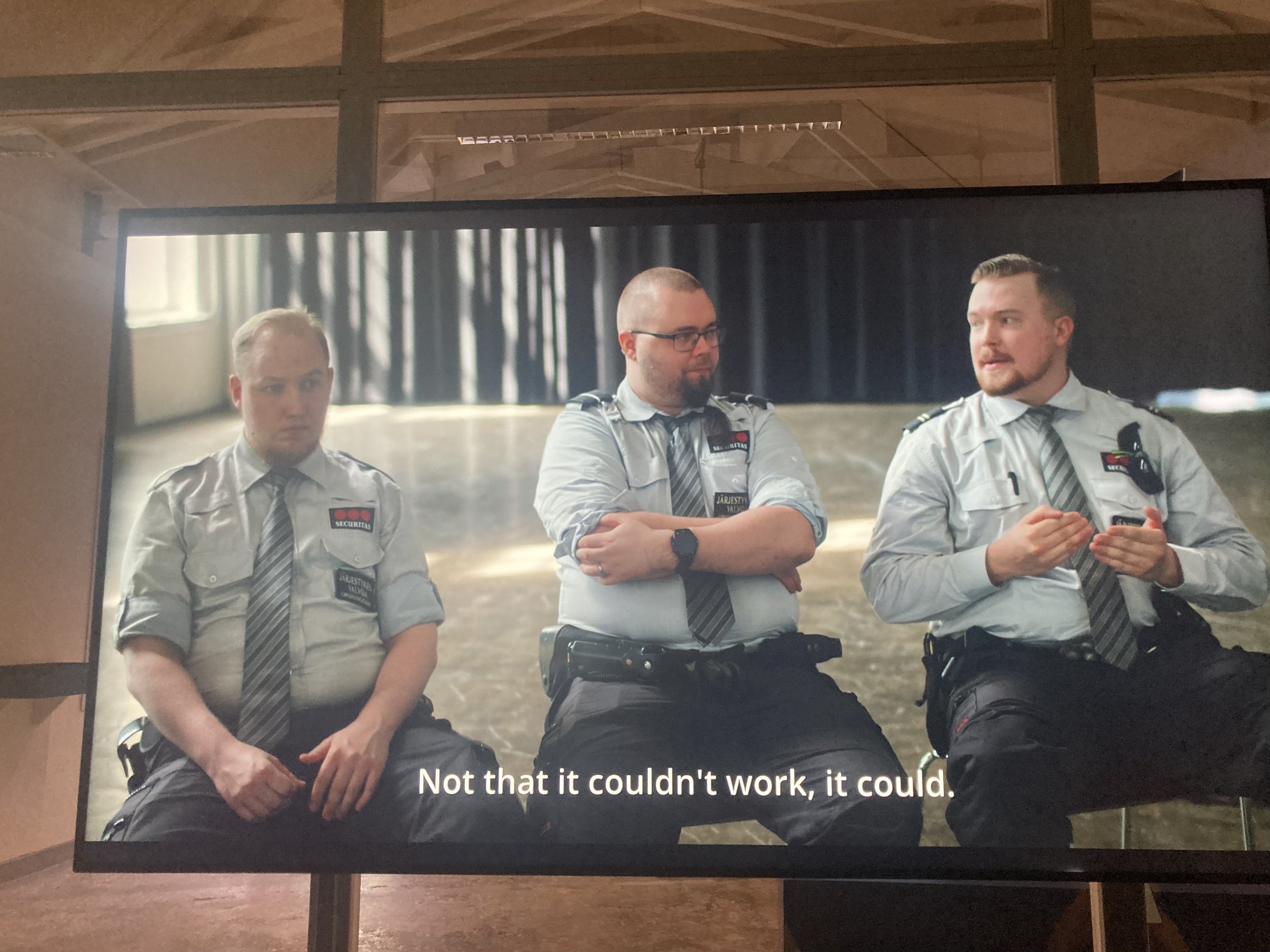

Alvar Alto’s furniture-like pavilion is an artwork itself (you feel like you enter a modernist treasure chest) and Pilvi Takala’s work doesn’t try to aesthetically compete with it in any way. The space is divided by a wall of mirrors. Only after exiting and entering on the back side, one realizes it’s a one way mirror. From here one can observe the visitors in the space one was just in. A fellow visitor nocks on the glass to attract the attention of her husband on the other side, but he just looks confused around. The power is all on this side of the glass.

The work is about shopping mall guards, with first an introduction through a text-message back log. To make the work the artist worked as a certified guard for several months. Not only her observations, but also her friendships created among colleagues are crucial. Just from reading the short messages, I feel the tention. She’s not really undercover and the leadership knew about her work, but it seems like a precarious position to put herself and others in.

In the second room there is a video showing a process between the guards she befriended and actors playing people they interact with, and they’ve discuss and tests out their ways of executing their power in less violent ways. It’s a video that is educationally useful, and it can be interpreted in many ways, but it’s also a most basic piece about bodies. How do you approach the other when you have the power? How do you safely approach someone with power, when you see what they do is wrong?

The fellow visitor who nocked on the one-way mirror forgot to reflect upon her position as the one with oversight. Her confused husband on the other side has no way to understand and react accordingly. It’s a simple mirror image, but it feels most relevant to all of us.

The second pavilion I want to write about is not in the exhibition area, but in an old, de-scarified church in the city. It’s hot and we walk far to get there, so already entering the cold, pillow filled space feels like a relief. Here Melanie Bonajo has created a world of beautiful rainbow colors, and it feels a lot more like a re-sacrificed than a de-sacrificed room, though in a seemingly completely new way.

A huge video screen is full of bodies. Naked bodies. Touching bodies. Bodies of different size, color, gender and shape, all safely interacting. Voiceovers tells personal stories about learning to receive touch freely and joyfully. It’s sexy, but not in a sexualized way. When we are there, small kids play around on the pillows, and an old couple walks slowly around in aw. The title of the work is “When the Body says Yes”, and it’s like the whole room is a body that sings its Yes out loud, but in the most tender way.

One scene in the film is different: hands stretch out harshly towards someone, but the body shouts a clear “No”. It knows how to reject what doesn’t feel good or safe; only then can one move on to the “Yes”.

Body acceptance and safe spaces are topics often discussed in social media and the news, but this is not a space for discussion or judgement. The colorful, fun and even holy form of the work fills the space completely. A space is created where power relations are put on pause, and even if many sorrows are allowed in, they are not in the way for blooming right now. Little do I know that I will find similar themes in Giotto’s 1303 chapel the following day.

I realize I’m not the most critical viewer here, partly because I was high on the holiday pleasures of a beautiful city and delicious food when I was there. But it’s not to be forgotten that a big Yes also can be a protest. And when I leave the dark, cool and soft space, I’m again in a world where this Yes is not available for all.

Day at the Biennial

I came to the exhibition The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani, very unprepared, so a quick look in the bookstore was not a bad introduction to what I could expect; the catalogue is as thick as a stack of three telephone books from my childhood, there are lots of books on famous female artists from the last 100 years and a poster that reminds me of 1970s theater aesthetics.

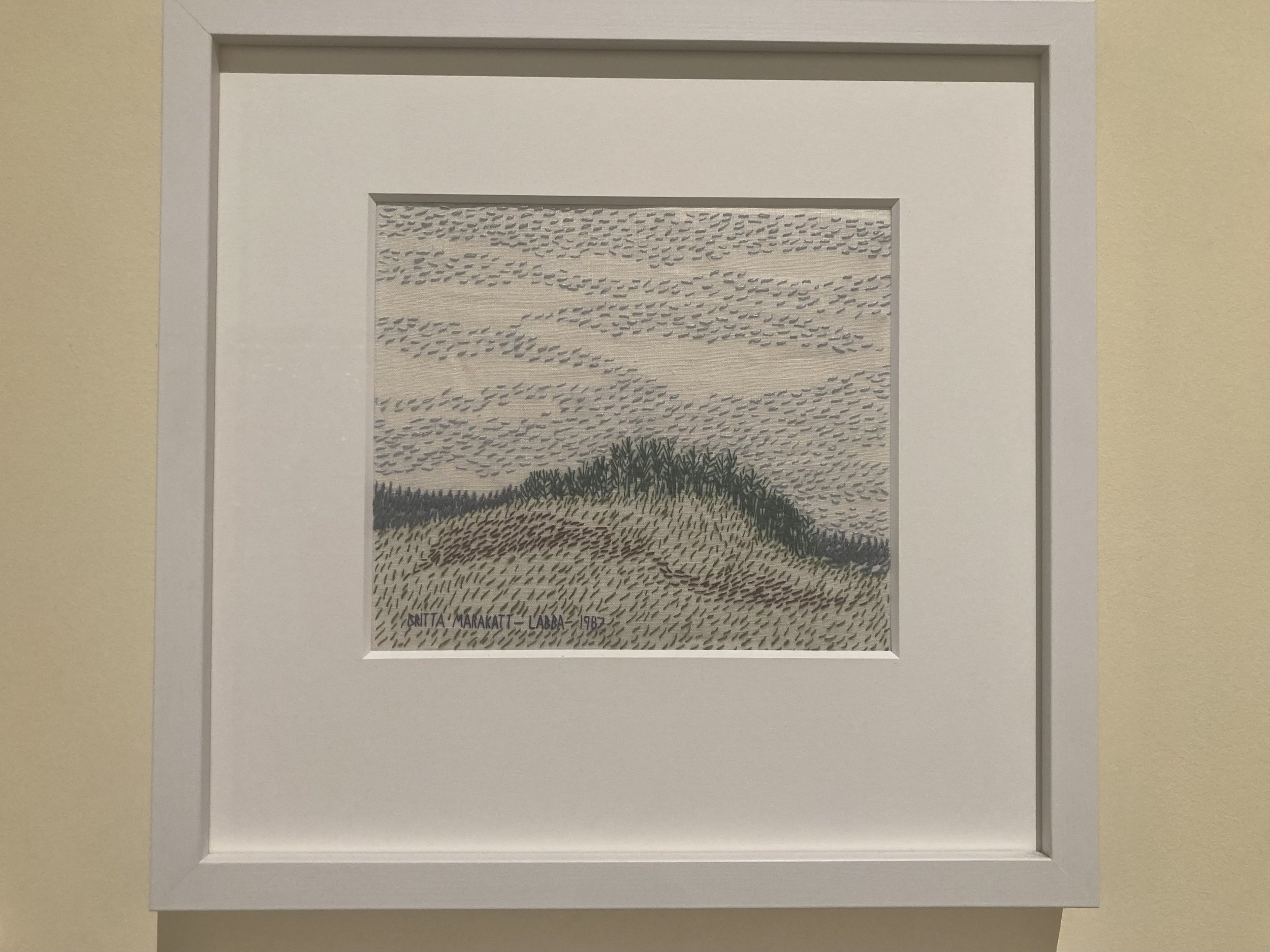

Inside the Arsenale venue the spaces are big, but every centimeter seems planned out and honed. There is a smooth flow of big, medium- and tiny-sized art works, and the mix of old and new doesn’t feel contrived. And at least among the newer works, the artists are not the obvious superstars. Several artists are represented by work they did late in their life. Painting by Ficre Ghebreyesus (and a random visitor’s dress) followed by embroidery by Britta Marakatt-Labba.

It’s not like the old is there only as a backstory, but at its best the new works can help in reading the old with fresh eyes. Bridget Tichenors surrealism from the 1950s looks very old and fresh at the same time, as do old plant drawings and body part models.

Sculptures, embroideries, drawings, paintings, a little purse by Sophie Tauber Arp, modernist rugs by Safia Foudhaïli, a new, extremely well made huge tapestry by Igshaan Adams, it might be pretty and soothing, but wall texts reveal artists also engaged with activism and education.

In the middle of all this colorful material perfection I laugh to myself that I wouldn’t be surprised if I suddenly saw paper flowers in the mix.

Turning around the corner, and there they are! Tetsumo Kudo’s fluorescent giant crepe paper work Flowers, made in 1967/68.

Pretty as any flowers, frightening as nature gone terribly wrong.

Towards the end of this venue where a huge cat tale peeks out of another room, I notice a friend from back home, and it feels wonderful chatting away a little. The mix of strange and homey is complete.

There are more flowers over in the other part of the exhibition in Giardini: I have forgotten the artist’s name, and if I remember right it’s an older 20th century watercolor, even if it looks as new as any. Too clichéd in most contexts, but here it works.

This is a 1937 surrealist photography for a children’s book by Claude Cahun, usually more known for her self portraits. It’s great to see lesser known works, but sometimes the most obvious and famous works work wonders in the context, like Rosemarie Trockel’s Untitled from 1985. So simple, but the funniest comment on painted linen canvas I can think of. What is really a sign of quality?

It’s such a classical, old fashioned show, even if little here was seen in any of those classical old fashioned shows before it. The themes of complicated bodies, nature dissolving and good and bad dreams coming alive are relatable for most, but I suspect that the audience that this show speaks to most forcefully is perhaps the most faithful audience of all, women like me who aren’t so young anymore.

Swallowed, but not consumed

We went to Venice only for the Art Biennale, I wouldn’t have come otherwise. (We have canals at home). It’s obviously pretty, especially the light, and magical when getting lost in the narrow alleyways. But we are flooding the city.

Not only sweaty people, but art commercials too. Every grand facade seem to be clad with a biennale poster or banners with some famous name. Give this city I brake is the thought in my mind. It’s swallowed by us, and it’s hard to see what is left of it.

But by day two, after we accidentally meet friends we haven’t seen in years and have Negronis on a green terrace by the water…

… and after we make a big effort going out to Lido for a five minute evening swim, I start to get around to it.

The hotel for our short stay has a spartan 1950s style, and is partly run by the nuns who owns it.

It has a classical canal side facade, but is cool and clean and untouched inside, and the balance between visitor and local interests seem balanced out. Our room has three narrow beds in a row, and somewhere across the canal someone plays on a harpsichord.

The last of the two mornings, we start out with caffe at a stand under cicada filled trees by the busy bus station, and a cold drink does wonders for the exhausted kid, then we push on with our program, before we have sprits in a narrow street where old Grandparents carry home their weekend shopping.

At lunch time we choose a random side path of a souvenir filled street, and find ourself in a Jewish neighborhood. Glimpses of actual life happening. At a square we sit down and eat homemade (and definitely not kosher) pasta and I cry a little because I cant believe how lucky I feel. Just enough Stendal-syndrome to feel very fine. Venezia - we travelers flood you, but you are still so good to us.

Roma, Roma, Roma.

Ruins everywhere, and medieval, renaissance and baroque times in layers above, walls looking like some scenographer worked very hard to create the right patina, but it was just time that worked hard on it.

In the Basilica of San Clemente an Irish priest in the 19th century dug himself down through a hole in the wall of his old church and found an even older church below, and then a cultic site and Roman homes below there again. The hole is still there, like a real version of the fresco of Jesus crawling down into the underworld just meters away from it.

We “did” tons of sites. But being a tourist isn’t only looking. I like the play, like eating dinner picnic style by the door in the bedroom, because that’s where the light is best.

The last morning I walked around in our neighborhood, the fruit lady at the market thrilled I came back for more of the orange peaches. It surprises me how many craftsmen and -women are at work around in small shops, even in a touristy city center like this; leather workers, seat weavers, framers, mosaic makers, purse makers, furniture builders, butchers and bakers. And prices of both things and food seem frozen, half the price of similar things in Amsterdam.

It’s my third time in this city, every time for short visits, first time I was 17 and we had pasta, saw Colosseum and left after one night. We were too unprepared and too tired. The second time I walked through the Vatican breastfeeding my one year old in the midst of the crowds to avoid a screaming baby: - The way God wants it, some clergyman told me. But I’m a simple traveler. Just as when I was younger it is those walks early in the morning around the block, going by a bar to buy bus tickets and coffee, watching the butcher work on a hanging piece like it’s been done since the beginning, that’s when I feel I see the city, that I’m a tourist the way I enjoy it the most.

Reflections, literally.

The train ride through the mountains went smoothly south, and the hour long stop over in Milan was as hot and boring as expected. When the train car to Rome had a trolley with an actual espresso machine on top, we knew we had already arrived.

The early 18th century house close to the tourist filled square Campo de’ fiori (that the air bnb auto translation correctly read as “appartement close to flower field”) is both charming and homey, and by surprise has air conditioning that makes us sleep heavy and dreamless through the night. It has a water fountain by the entrance door: with all the people stopping to fill theirs bottles it truly is a giving house. In the evening our shadows are reflected on the walls of the renaissance palace across the street, something I’m not shy to take as an invite to dance..

Floating

Floating down to the current of a river, that’s how the trip started. The bath house had closed for the evening, so we walked a little further up the stream and went into the water from a steep edge. It doesn’t take much skill or effort when the river takes the lead, and following our local friend, it felt safe even if the three of us where the only ones floating out in it. As we drifted down through the city, we watched people sitting at cafes or partying on the river bank. The evening sun stood low right in front of us. When we took ourself to the edge again, we all got small bruises on our knees from the sharp stones, and the soles of our bare feet got more than a gentle massage as we walked on the rocky path back to our clothes where we had entered the river further up.

The actual beginning of the trip obviously started several hours before, when we carried our backpacks across the market square at home as the vegetable guy was setting up his stand, before we crossed flat fields for hours in a full train. Only on the very end we started ascending low mountains, getting of to see our Swiss friends.

The next day was spent on a beach of the Lake Zurich, occasionally swimming out to the crowded floating deck and watching the guard give their instructions from their wooden row boat. Far away, beyond the crisp green lake, the high mountains looked more like clouds, signs of the alps our train would cross under the following day. But for now it was all about staying still, hanging out with the kids of friends, a quick stop at the local cactus garden being a cute little surprise intermission, where Edithcolea was the star of the day.

Train feelings

- Why, I ask myself, as I’m stressing around trying to do everything I need to do. There are so many relaxing places in the world, but I pushed for going on a trip that requires planning, packing, arranging, never resting, and still no guarantees it will actually work out. We could have chosen to go to a mask free place where the pandemic is just a memory. Instead we head back into it. We could have chosen for sea breeze or windy mountains, instead we’re going to the hottest, sweatiest place of Europe. Why? Of course I know why. It’s all about that feeling I hope suddenly will appear when the train leaves Central Station early in the morning. A feeling of beginning a journey. A feeling of movement, of not knowing, of losing control, of becoming part of a rhythmic heart beat stronger than my own, and just be a fleeting face behind a window in a long, heavy train passing by.

Volgermeerpolder

Many years ago, when I first passed it, I thought it was a secret military camp or something like that. From the outside it had a certain darkness to it. But later, when fences went down and I understood I could enter the area, I found nothing but a big, flower-filled meadow inside.

Since this land is a little higher than the surrounding fields, it has an almost mountain-like feel. The low, linear horizon surrounding it is interrupted only by a few farms and the blunt tower of Ransdorp, once drawn by Rembrandt, probably when it was the temporary hometown of his housekeeper and lover, Geertje Dircx. Also the high risers of Amsterdam are there in view, far away, the church towers of Zunderdorp, Broek in Waterland and Monnikendam, and to the east one can see what I think must be the buildings of a completely different city, Almere, though the latter structures are only visible on the clearest days.

There is history in this blooming hill. A poisonous one. Buried in the ground lies some extremely toxic materials, among them dioxins. Barrels of chemicals were unlawfully deposited here by big business in the 1960s. Thousands of barrels. Since the area earlier had been used to dig out peat to be dried for fuel, it already had big sunken areas, and I guess it was these that were used by the city and by commercial enterprises as a land fill. Ironically peat, like the one that was first was removed to be burned, is one of the best capturers of carbon dioxides. It is a ground that was marred twice.

Then in recent times, and through major endeavors, the toxic ground was covered in layers of huge sheets and masses of soil. On top came fresh water and vegetation. To make new peatland probably takes a very long time, but there are plenty of wet areas, and to one side a wide, dry grassland with a path across. A crossing over some water is built as concrete stepping stones, otherwise there are few signs of it being a public park. The borders aren’t marked and there are no visible barriers between the hill and the lower landscape.

The grass is kept mostly uncut to the pleasure of beasts and birds. How well the beasts in the ground are sealed in, I wouldn't know. But this year, for the first time, I saw one of the marsh orchids that are plentiful outside the hill, also grow on it. Like an old garment most carefully mended to last many more seasons, it seems to work for now.